I’ve always been fascinated by religion. My own—I maintain that the Talmud is the world’s first fix-it fic—and others, real and imagined. The way that the same underlying morals and ideas show up again and again, justified through different cosmologies, canons, and deities—and the way the same sets of core beliefs are used to justify wildly contradictory obligations.

Delve deep enough into linguistics, and eventually you’ll want to try constructed languages, with new vocabularies and grammars that illustrate the principles and limitations of those that occur naturally. Spend enough late nights arguing theology, and you start wanting to make up your own. My first-ever business card was for the half-joking Discount Deities: custom pantheon creation and appropriately biased origin myths.

For the Innsmouth Legacy books, I’ve had a lot of fun adapting Lovecraft’s Mythos into a believable faith that isn’t just an apocalyptic cult. (Not that there aren’t plenty of those in the real world.) Or rather, into three or four believable faiths, with the implication of more in the background. After all, a religion can’t last for a few billion years and spread to multiple planets without hitting a few schisms on the way. In Deep Roots, Aphra Marsh meets aliens who worship the same gods as her, but have very different ideas about What Nyarlathotep Wants From Us. She even participates in one of their sacraments—not actually the healthiest choice she could have made.

A good fictional religion, like a real one, provides appealing insight into our place in the universe. It may even answer yearnings that existing faiths have failed at—at least for the author, and sometimes for the readers. So, just as many constructed languages accrete communities of speakers, imagined religions spill over into real practice. These new faiths start out serving the purpose of their stories, but not all have stayed fictional.

Robert Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land

Religion: The Church of All Worlds

Religion: The Church of All Worlds

Core Beliefs and Practice: A human-friendly version of Martian spiritual practice, the Church blends free love, language studies, inhuman patience, and rituals that revel in Earth’s bounty of water. Study hard enough, and you’ll pick up psychic powers, allowing you to demonstrate the truth behind, “Thou art god” in some pretty dramatic ways.

Ontological Status: I’ve been to a water-sharing ceremony, and it was pretty cool. No orgies were involved, but then I’m not part of a nest.

Kurt Vonnegut Jr.’s Cat’s Cradle

Religion: Bokononism

Religion: Bokononism

Core Beliefs and Practice: All religion is based on lies, and therefore you might as well be self-aware in finding harmless untruths that will make you happy, and make you treat other people well. Footsie is a sacrament.

Ontological Status: I don’t know any Bokononists, but that doesn’t mean they’re not out there. (If I said they were, would I be being a Bokononist myself?) [ETA: Apparently there’s a camp at Burning Man. Which I’ve missed due to my policy of only camping in habitable environments.]

Rosemary Kirstein’s The Steerswoman

Religion: The Order of Steerswomen

Religion: The Order of Steerswomen

Core beliefs and Practice: The Steerswomen may be thoroughly secular humanist, but they certainly seem like a monastic order, and treat their work and their vows as sacred. Their goal is to learn everything there is to know about the world. To this end, they swear two things. First a steerswoman must answer any question asked of her, and answer it honestly. Second, she must always strive to learn the truth—and the only questions she won’t answer are those asked by people who’ve refused to tell her the truth.

Ontological Status: The author has one of the rings.

Lois McMaster Bujold’s The Curse of Chalion

Religion: The Five Gods

Religion: The Five Gods

Core Beliefs and Practice: When gods are real and interventionist, it’s easy to get so caught up in pantheon politics that you miss the day-to-day practice of worship. Not so the Hugo-nominated Chalion series. The religion of the Five Gods seamlessly mixes ritual, magic, and direct contact with deity. Take the ominous-sounding Death Omen, which tells mourners which god has taken up the soul of the departed. Depending on where you live, five dedicats dressed as sacred animals may carry out an ornate dance to communicate the gods’ will. Or alternatively, you could release a basket of five kittens wearing different-colored ribbons, and see which one approaches the corpse. It works just as well either way.

Ontological status: Safely confined to the page.

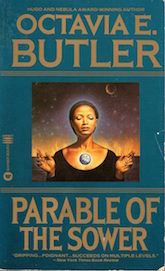

Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower

Religion: Earthseed

Religion: Earthseed

Core beliefs and Practice: Michael Valentine Smith says, “Thou art god.” Lauren Olamina says, “God is change,” and encourages her followers to “shape god.” In the midst of a world sliding towards apocalypse, she preaches that “the destiny of Earthseed is to take root among the stars.”

Ontological Status: Parable takes place on a near-future Earth with a growing environmental crisis, increasing social inequality, and someone running for president with the slogan “Make America Great Again.” Perhaps it’s no surprise that a few groups and movements have sprung up drawing on Olamina’s teachings. But that’s another column…

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots (available July 10th, 2018). Her neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Dreamwidth, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

There is the original Game of Thrones, the grand daddy of epic fantasy, and the ur example of fictional religion.

The Bible: by Various.

Lot of people have been taking that one too seriously for far too long. Cant wait until they find that missing front page.

I’d totally sign up to be a Divine of the Bastard. The problem is that the religion doesn’t really work without actually having the Five Gods kicking around.

The Bene Gesserit are a “religious” order. Several other adapted/invented religions in the Duniverse.

Elisabeth Vonarburg, In the Mother’s Land/ The Maerlande Chronicles

https://www.tor.com/2009/07/29/history-language-identity-elisabeth-vonarburgs-the-maerlande-chronicles/

The Taoism-inspired religion practiced by the Gethenians from The Left Hand of Darkness.

Re #1 : Most, if not all, Earth religions can be said to be invented to a certain extent.

Dr Liz Williams’ Chen books. A very different heaven and hell, with demons [well, at least one] serving in the police force.

Steerswoman sounds rather intriguing from that blurb. I’d come across it before but was put off by the font on the cover looking amateurish. Maybe I’ll give it a go now.

I’ve enjoyed Parable of the Sower, especially the God is Change aspect. Think it would be a great read for teenagers.

@2, You just want the polar bear.

Max Gladstone’s Craft Sequence has one of the BEST takes on religion. I really enjoy it.

@6 That is what I’ve been telling people for years.

There is a song about it:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wtJPuu5TE3E

Interesting that Scientology didn’t make the list.

>>invented

>>religions

Bit of a large difference between “Invented” and re-invented; so I can’t complain that The Illuminatus Trilogy isn’t in there; but nevertheless; as ontology recapitulates philogony; “All Hail Discordia!”

@8 Yes. Polar bears. That’s totally it.

“A Canticle for Leibowitz”

Beebo lives!

To go a different direction from the snark, the Five Gods strike me as one of the most successful depictions of realistic character relationships to a fictional religion in fantasy. Probably the biggest strength of the series.

While we’re on Hugo Best Series, also a good time to bring up Jackson Bennett’s The Divine Cities. Though I do think that the depiction of religion is rather shallow in City of Stairs, it picks up much more heft and numinous effect in City of Blades.

Philip Jose Farmer had always a lot to say about religion: Night of Light for example.

The cult of the Shrike in the Hyperion Cantos.

Cordwainer Smith and the underpeople cults in his Instrumentality of mankind cycle.

All the Eternal Champion works from Moorcock and the big eternal struggle between the forces of Law and Chaos.

Also at least a nod should go to the Discworld religions: I mean, Small Gods!

Raising a little more hell this time: the Church in His Dark Materials. Pullman’s vision of both the Church and its basis in the Almighty aren’t “generic Christianity for the purpose of arguing against Christianity”. They’re more specifically the imaginary worship of a being who has falsely set himself up/allowed himself to be represented as the hardline Calvinist version of god, i.e. a being who must be worshipped solely because of his position in the cosmic hierarchy. It’s a significant point that Pullman locates the Magisterium in Geneva, not Rome.

@16. MByerly: Praise Beebo!

Amazes me how many people don’t get that reference. Guess viewership of Legends isn’t widespread enough, even among genre consumers.

It may have had a weird effect on me and my girlfriend. We sometimes talk about what Bear (a stuffed polar bear with red hearts I got her for Valentine’s day) has been up to.

@20 It’s their loss not to know the true God of War in all his blue furriness. Praise Beebo!

Anyone in need of cheering up, and who doesn’t these days, should watch Season 2 of LEGENDS OF TOMORROW in all its bonkers awesomeness.

i like much of what is up here, though not Heinlein.

octavia Butler is so relevant these days it is scary.

i also have a weakness for Sharon Shin’s angel series.

praying to the terraformers by flying and singing? Anyone?

second Max Gladstone.

.how about Charles stross’s laundry books? Icky/horrific faiths, but still…

also, don’t the Culture books by Banks offer some interesting tales on religion?

N. K. Jemisin’s Hundred Thousand Kingdoms

It’s a significant point that Pullman locates the Magisterium in Geneva, not Rome.

Because part of the backstory of the books is that, in Lyra’s world, John Calvin reconciled himself to the Catholic church and became pope. The Church in the Pullman books is explicitly the Catholic church. “Magisterium” refers to the pope and his cabinet, and to papal authority in general, just as it does in real life.

I often say the prayer to the Bastard from Paladin of Souls now:

”And the Bastard grant us… in our direst need, the smallest gifts: the nail of the horseshoe, the pin of the axle, the feather at the pivot point, the pebble at the mountain’s peak, the kiss in despair, the one right word.”

It seems deeply relevant to me as someone who has battled depression and has found that the smallest gifts have been those which have kept me going. In my youth, I loved Stranger in A Strange Land, but as I grow old, I wear the Bastard’s white and pray his prayer.

@25. That was deeply moving. I myself appreciate the Bastard’s sense of humour.

There is also Watership Down, the rabbits worship of Frith and Frith’s gifts (or lack thereof at times) to the rabbits; not to mention the rabbit folk tales of El-ahrairah the rabbit trickster god, are all integral to the world building and plot of the book.

Would The Force be considered a religion?

I’d like to read books about people actually inventing religions.

I also love Shinn’s Jovah books, where you can see the results of the worship. It’s just that the “god” is something…else.

One of my favorites is Jacqueline Carey’s “Kushiel’s Legacy” books. I love the precept of Blessed Elua, “Love as thou wilt”, and how the D’Angeline deal with other religions. “I respect that you have your own god/s, but they are not mine.” I really wish we could have more that in the real world.

@25, that is a beautiful one, though Cazaril’s invocation in The Curse of Chalion is the one that really gets to me (“god of justice when justice fails”).

Ancillary Justice by Leckie also has lots of invented religions in it – including the Radch religious belief that unusual events always have a meaning. This becomes a plot point because Breq is hanging out with Seivarden, who had something remarkably unusual happen to her in the relatively recent past.

“I’d like to read books about people actually inventing religions.”

Dune is the obvious one, no?

In Ursula K. Le Guin’s novella Paradises Lost Kim Terry, son of the last earthborn person on the generation ship Discovery, founded the creed of Bliss after his mother’s death. His followers, who call themselves angels, gained in numbers until they almost manage to prevent the colonisation of the ship’s destination planet. Here’s an excerpt from a speech given by Patel Inbliss, their spiritual leader at the time of the story:

The novella follows two friends, Liu Hsing and Nova Luis, as they grow up on the ship, slowly become aware of the danger the angels pose, and fight for the right to fulfil their original duty to colonise the soon-to-be-reached planet.

@34/janajansen,

Now there’s a metaphor – the purpose of religion is to keep your feet from ever touching the ground.

“If you have to worship something, worship life!” – Paul Atreides

“The mystery of life is not a problem to be solved, but a reality to be experienced!” – Bene Gesserit Saying

Stranger in a Strange Land has two invented religions– the other one is the Fosterites.

Isle of the Dead by Zelazny has an invented religion in which it is possible to become a god.

There are at least two religions in the Game of Thrones series.

@29/johnarkansawyer, that’s exactly what Parable of the Sower is, along with the sequel, Parable of the Talents.

How is Dune not in this list…

Good question !

I have come to have a special appreciation of books that manage to have actual gods and actual miracles, without those ending up the complete solution to … everything. Bujold does this really well, but I’d also like to put in a recommendation for Maya Bohnhoff’s “Mer Cycle” (staring with “The Meri”), and Elizabeth Moon’s “Paksenarrion” series.

Thanks for the signal-boost — but the Steerswomen, a religion? Rather the exact opposite, I’d say!

And as for their ontological status, at least two of their principles have real-world adherents.

Gaining knowledge of the world through observation and reason: scientists.

Sharing knowledge freely to all who ask: every librarian ever!

Rosemary @@@@@ 41: I’ll admit it’s a bit of a stretch, but I do think of their order as distilling out the spiritual and moral practice of science, with more focus and clarity than real world scientists manage at times. Or at least, when I was a professor of experimental psychology, I’d go back to those books when I felt like the core of my work was obfuscated behind grant applications and committee meetings. For some people the most important part of religion is a set of beliefs that one must accept without evidence, and on those grounds the Steerswomen do represent the opposite. But for others, the important part of religion is a set of principles for having a good relationship with the universe and other people–guidelines for what to do with one’s observations of reality. And at that, the Steerswomen excel.

@42: R.Emrys: regarding religion… I was watching a Republican politician on TV this morning defining his stance as religious. He embraced both sides of your definition. A belief in a higher, invisible power from which emanates moral decision-making. He then defined faith as treating others well, while putting yourself in their shoes.

For his latter points, everything he said did not need faith in the mix at all. That word doesn’t mean what he thinks it means. It’s empathy. I think of empathy as a spectrum. The closer you are to one end, the more likely you are to do for and help others. Closer to the other end, you’re likely to be far more cold-hearted. Basically from altruism to pure selfishness. This tends to align pretty well with political ideology.